Credit: An NRD41 dropsonde, like the ones dropped into Hurricane Melissa, with Hurricane Irma in the background. Dropsonde technology is developed by NSF NCAR and manufactured by Vaisala. (Image: Holger Vömel/NSF NCAR)

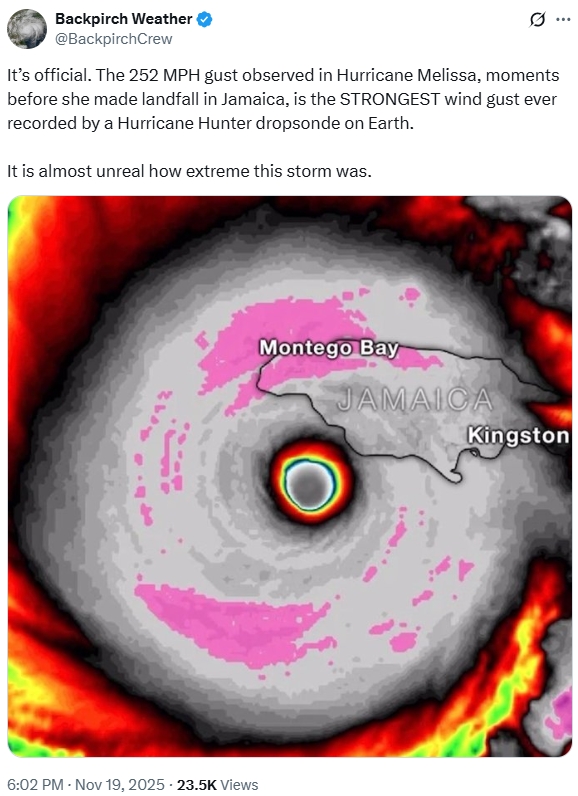

Record-Breaking Winds Confirmed for Hurricane Melissa. NSF UCAR has the post; here’s an excerpt: “As Hurricane Melissa approached Jamaica last month, a NOAA Hurricane Hunter airplane dropped a fleet of weather instruments called dropsondes into the depths of the storm. Each dropsonde parachuted through the raging winds and pouring rain, beaming a stream of data readings on pressure, temperature, humidity, and wind back to the plane. Right before one of the dropsondes plunged into the ocean, it reported a measurement that caught the team’s attention: a wind gust reading of 252 miles per hour. Had they just captured the strongest hurricane wind ever recorded by a dropsonde?…”

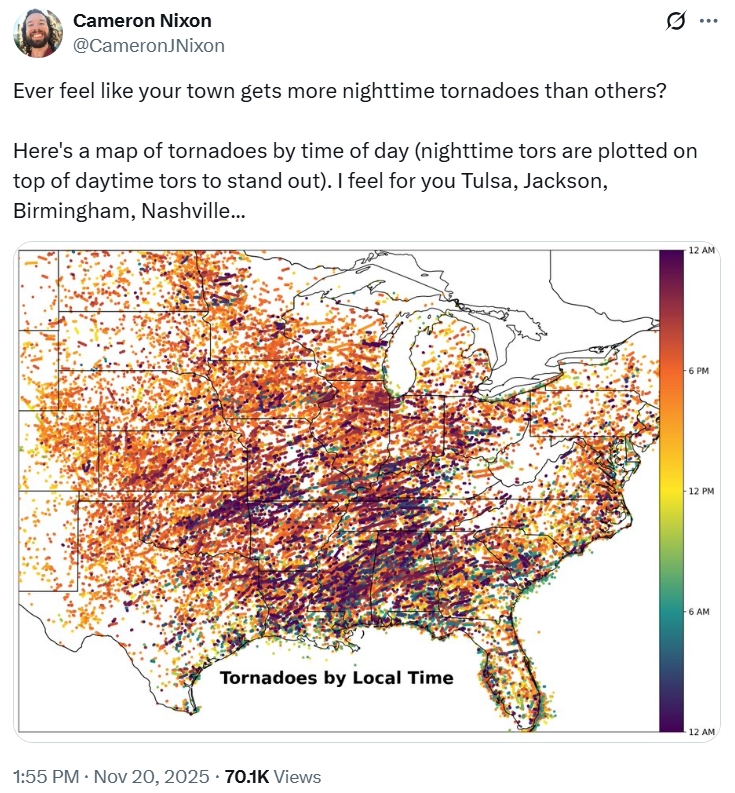

Credit: X

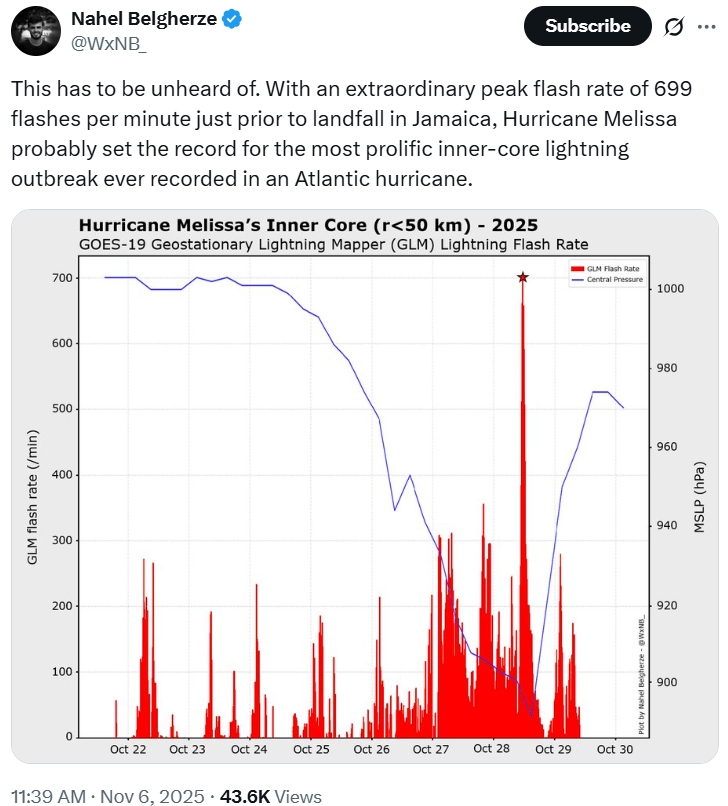

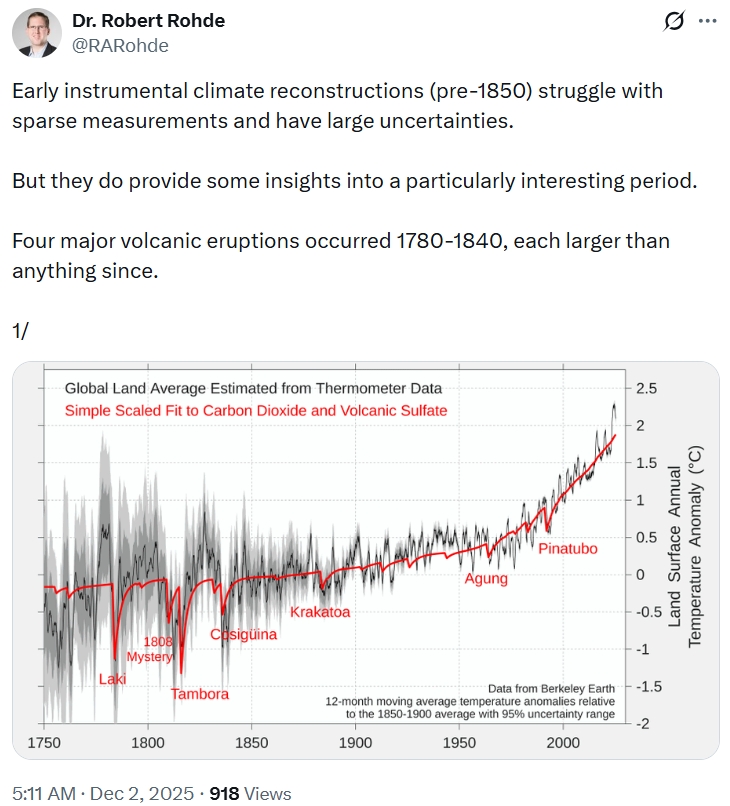

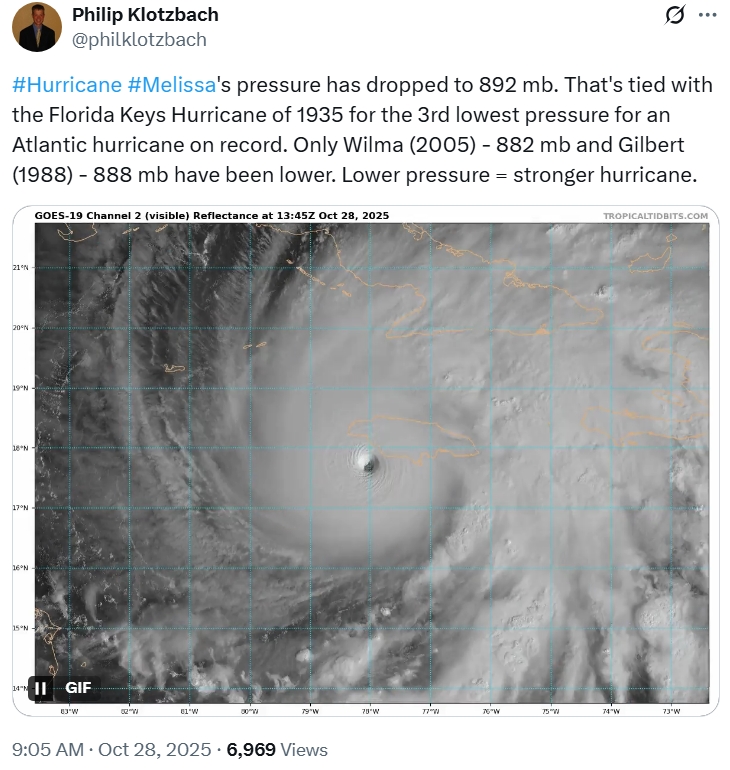

The Caribbean has a Super-Hurricane Problem. Extreme Category 5 Hurricane Melissa was similar to super-typhoons in the western Pacific basin and it may be a trend, according to Yale Climate Connections. Here’s the intro: “In the western Pacific, there is a special name for high-end Category 4 and 5 typhoons with winds exceeding 150 mph (240 km/h): super typhoons. No equivalent terminology exists in the Atlantic for “super hurricanes.” But perhaps there should be, because these strongest of the strong storms are an increasing threat to the viability of living along the Caribbean, as they are expected to become increasingly common because of climate change…”

Credit: Brian McNoldy

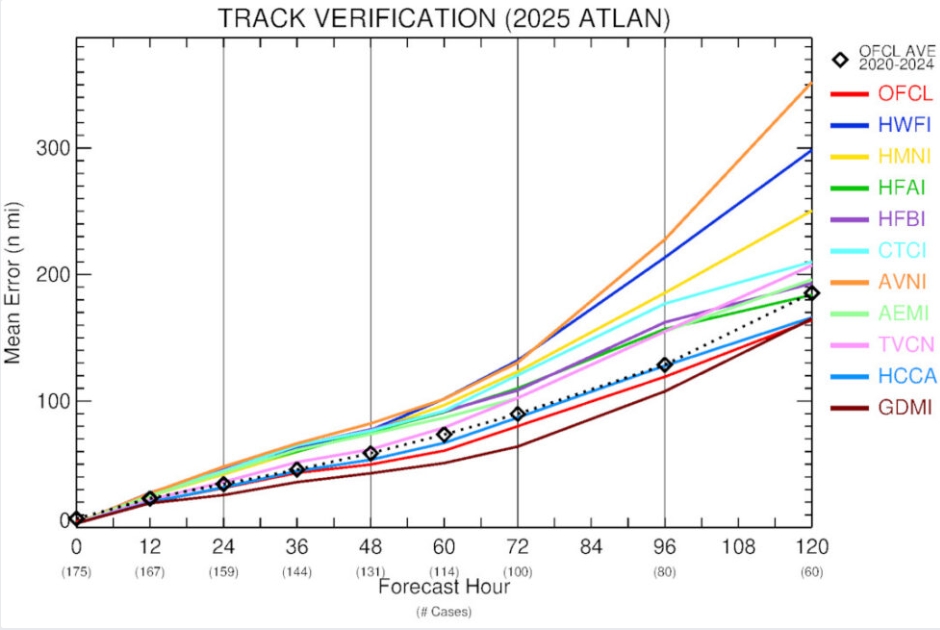

Google’s New Hurricane Model was Breathtakingly Good This Season. Yes, the AI model from Google DeepMinds performed best, according to a post at Ars Technica: “…The dotted black line shows the average forecast error for official forecasts from the 2022 to 2024 seasons. What jumps out is that the United States’ premier global model, the GFS (denoted here as AVNI), is by far the worst-performing model. Meanwhile, at the bottom of the chart, in maroon, is the Google DeepMind model (GDMI), performing the best at nearly all forecast hours. The difference in errors between the US GFS model and Google’s DeepMind is remarkable. At five days, the Google forecast had an error of 165 nautical miles compared to 360 nautical miles for the GFS model, more than twice as bad. This is the kind of error that causes forecasters to completely disregard one model in favor of another...”

Credit: Hurricane Imelda over Bermuda on Oct. 1. NOAA

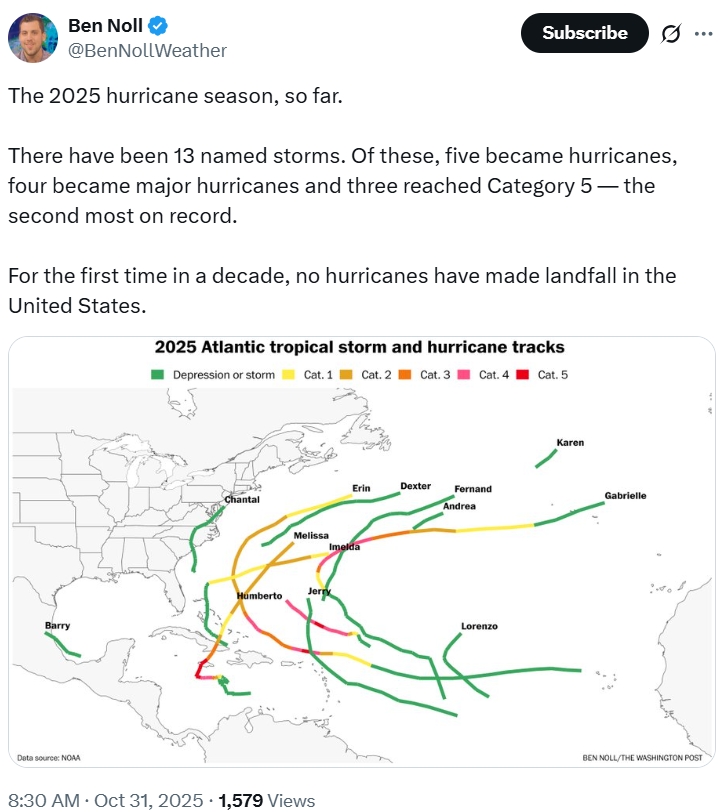

As Hurricane Season Ends, Researchers Note Its Surprises. Here’s a clip from a post by NBC News: “…Hurricane season comes to its official close on Nov. 30. In some ways, 2025 fits what researchers expect to see more often as the climate warms: Hurricanes continued forming late into the season and several intensified at extreme rates to produce some of the most intense storms in history. But in other ways, it was simply odd. Fewer hurricanes formed than experts predicted, but almost all of them became major storms. And the continental U.S. was spared a landfall for the first time in a decade. The surprises were a reminder of hurricane season’s unpredictability — particularly in a warming world — even as forecasting gets more accurate...”

Traditional Weather Forecasting is Slow and Expensive. AI Could Help. I’m not totally onboard yet with non-physics-based weather models but it’s hard to argue with the results from Google’s DeepMind model in 2025. Here’s more perspective on the advantages of AI-driven models from Grist: “…This physics-based technique, developed in the 1950s, requires multimillion–dollar supercomputers capable of solving complex equations that mimic atmospheric processes. The intensive number-crunching can take hours to produce a single forecast and is out of reach for many forecasters, particularly in the developing world, leaving them to rely upon data produced by others. Tools driven by artificial intelligence are becoming a faster, and in many cases more accurate, alternative easily produced on a laptop. They use machine learning that draws from 40 years of open-source weather data to spot patterns and identify trends that can help predict what’s coming…”

Imagery credit above: CIRA, Colorado State University.

Credit: NOAA

Flood-Prone America is Seeing More People Move Out Than In for the First Time Since 2019. Yahoo! Finance has the post; here’s an excerpt: “…Major hubs in coastal Florida, Texas, New York and Louisiana were driving forces behind the national net outflow last year. Miami-Dade County, where over one-third of homes face high flood risk, saw 67,418 more people move out than in—the largest net outflow among the 310 high-flood-risk counties Redfin analyzed. Next comes Harris County, TX (home to Houston), which saw a net outflow of 31,165. In third place is Kings County, NY (home to Brooklyn), which saw a net outflow of 28,158. Also notably on the top 10 list with a net outflow of 4,950 is Orleans Parish, LA (home to New Orleans), where 99.1% of homes face high flood risk—the highest share in the nation…”

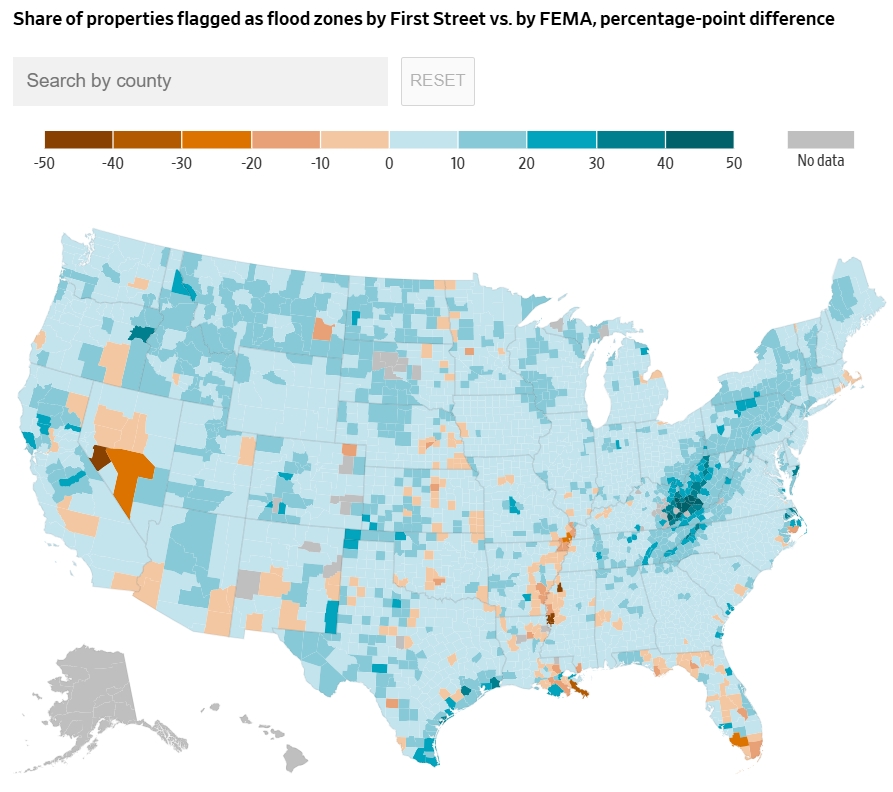

Note: First Street uses forward-looking projections and includes floods from rainfall alone; FEMA uses historical data and delineates flood zones near rivers, oceans and other bodies of water.

Sources: Federal Emergency Management Agency; First Street

Alana Pipe/WSJ

It’s Getting Harder to Figure Out Whether You Live in a Flood Zone or Not. You may not even realize you live in a flood zone, according to The Wall Street Journal; here’s an excerpt: “…Data provider First Street estimates that around eight million properties lie in areas the Federal Emergency Management Agency designates as flood zones, with a 1% or higher chance of flooding every year. The firm found another nearly 13 million properties outside the zones with the same level of flood risk. The endangered areas not flagged by federal officials include about a half-million properties in New York City, Houston, Los Angeles, Philadelphia and Chicago…”

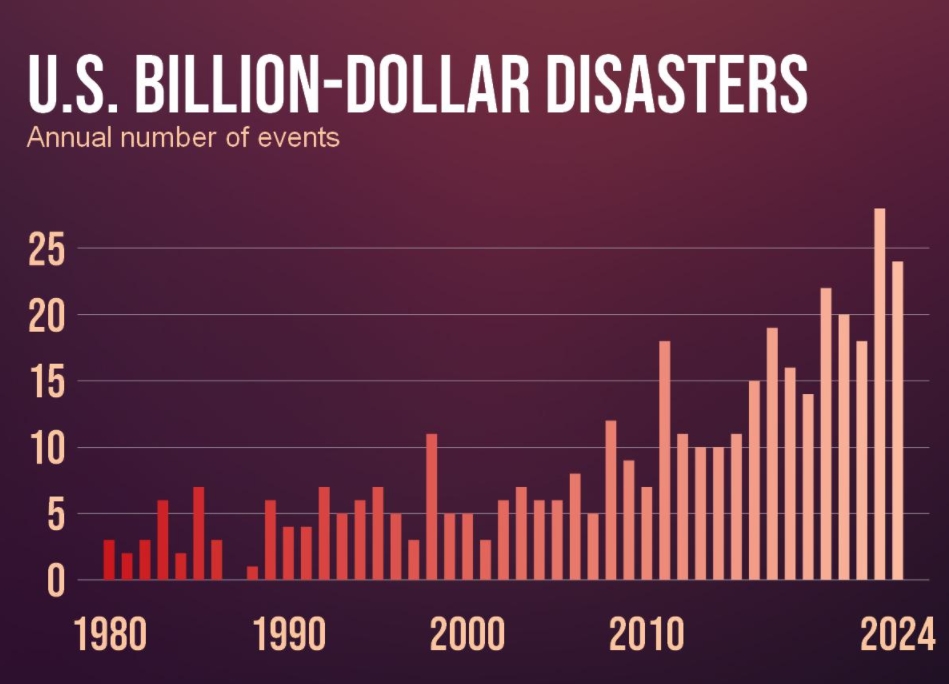

Credit: NOAA, Climate Central

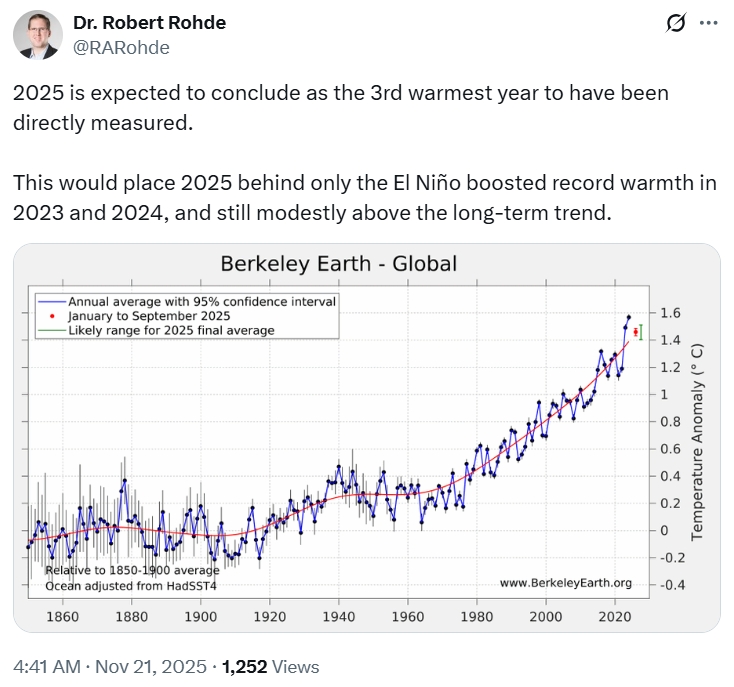

What Climate Change Will Do to America by Mid-Century. Here’s an excerpt of a post from The Atlantic: “…I didn’t make up the problems,” Butler wrote in an essay for Essence in 2000. “All I did was look around at the problems we’re neglecting now and give them about 30 years to grow into full-fledged disasters.” That same year, she said in an interview that she dearly hoped she was not prophesying anything at all; that among other social ills, climate change would become a disaster only if it was allowed to fester. “I hope, of course, that we will be smarter than that,” Butler said six years before her death, in 2006. What will our “full-fledged disasters” be in three decades, as the planet continues to warm? The year 2024 was the hottest on record. Yet 2025 has been perhaps the single most devastating year in the fight for a livable planet…”

5 Things That Set the 2025 Hurricane Season Apart. BBC Weather has a good summary of a very strange hurricane season in the Atlantic: “The 2025 Atlantic hurricane season will probably be remembered mainly for Hurricane Melissa and the devastation it caused across Jamaica and Cuba. But it was also a season of stark contrasts, with periods of relative calm and bursts of intense activity. The season managed to generate three Category 5 hurricanes – for only the second time on record, external. But then, during the typical mid-September peak, things turned “remarkably quiet” according to Dr Philip Klotzbach, author of the seasonal hurricane forecast. Also notable, it was the first time since 2015 when no hurricane made landfall in the United States…”